A prolific spinner, teacher, and former spinning store owner, Beth Smith has bought more fleece than a small yarn company. Knocking on doors at likely looking farms, finding wool through word of mouth, or cyber stalking rare breeds, Beth has tried it all. In her Spin Off Winter 2017 article “Fleece Sleuthing” she shares some lessons she’s learned.

If you have to buy without seeing . . .

Sometimes it’s just not practical to drive to the farm, or maybe you want a specific rare fleece but the shepherd doesn’t have a website. In these cases, you can just take a chance and be ready to compost what comes in the mail. When you are buying this way, the price of the fleece is often pretty low, so just go for it.

Fleece that has felted on the sheep is known as “cotted.” It may be more easily detected by hand than by eye.

Fleece that has felted on the sheep is known as “cotted.” It may be more easily detected by hand than by eye.

I can think of two bad experiences I’ve had that paint a good picture of a wide variety of mistakes. (Of course, there have been more than two.)

One was many years ago, at the very beginning of my fleece-buying journey. I needed some Lincoln wool for my shop and was having trouble finding any nearby. One of the local shepherds sheared twice per year, so he didn’t have the longer lengths I wanted. Another local shepherd scoured all of her fleeces before she would sell them, and I was looking for fleece in the grease. I started to move farther away from home in my search, and I came upon a shepherd on the Lincoln Sheep Breeders website. It looked as though she had a large flock, but there was no website, so I called her on the phone. She mentioned that she had a pretty large amount of Lincoln lamb fleeces—about 60 pounds—all in one bag, and did I want to buy them? The price was good, and I reasoned that lamb fleeces would sell well. There was no photo, and in my eagerness, I neglected to ask some very important questions. First and foremost, I never asked about lock length. The wool arrived, and I hung my head in shame. The locks were less than 3 inches in length; Lincoln should be at least 8 inches for one year’s growth, so I expected these to be around 6 inches. When I contacted the shepherd, she said she had wondered if that would be an issue. I wish she had asked me, but I felt that the mistake was mine for not checking. I learned a big lesson there, and that wool went the way of the compost.

You probably need to get your hands on a fleece to determine whether it has a break. Snapping a lock close to your ear is the best test; if it has a “ping” tone, it’s sound; if it is fresh (shorn less than 6 months ago) and makes a crackling sound, it is tender. If it comes apart in your hands, it has a break, a weakness along the shaft.

You probably need to get your hands on a fleece to determine whether it has a break. Snapping a lock close to your ear is the best test; if it has a “ping” tone, it’s sound; if it is fresh (shorn less than 6 months ago) and makes a crackling sound, it is tender. If it comes apart in your hands, it has a break, a weakness along the shaft.

The second story happened less than two years ago. It concerns a sheep breed called Romanov, which is extremely hard to find in the United States. It is double coated, with a very soft undercoat and a supercoarse outercoat. I just wanted one or two fleeces to add to my collection, but I couldn’t find any in Michigan. I saw a few in a field while driving in Pennsylvania, but I learned that the shepherd always got rid of the wool, and I always managed to miss his shearing time when I was in the area.

Finally, I found a guy on Facebook. When we talked, he said that these sheep are usually used for meat and I wouldn’t like the wool. I explained what I do for my job, and he finally agreed to send me two fleeces and charge $5 per pound. The total was about $25 plus shipping. I was so excited when the fleece arrived, and I immediately opened the package. It was pretty messy and full of vegetable matter, so I took the box out to the back porch and dumped the fleece out. It was another sad day. The whole fleece was cotted. Cotting refers to when the wool felts before the sheep is sheared, and it’s impossible to use the wool. I didn’t even try to salvage it; I knew it was hopeless. Off to the compost it went. Again, I didn’t blame the shepherd. He wasn’t raising a spinner’s flock, so he wouldn’t know it was unusable.

Even last year, I bought some fleeces that were not great. One had a ton of scurf and another had a break. I bought both fleeces in person at a fiber festival, but I was in a hurry and they were breeds I needed, so off I went with fleeces that would be used to teach people what to avoid. I would not have written these fleeces off if I had paid top dollar for a coated fleece, but since these were pretty much bargains, I consider them investments in my education.

Sometimes there are undesirable results, but I have bought a lot more great fleeces than bad.

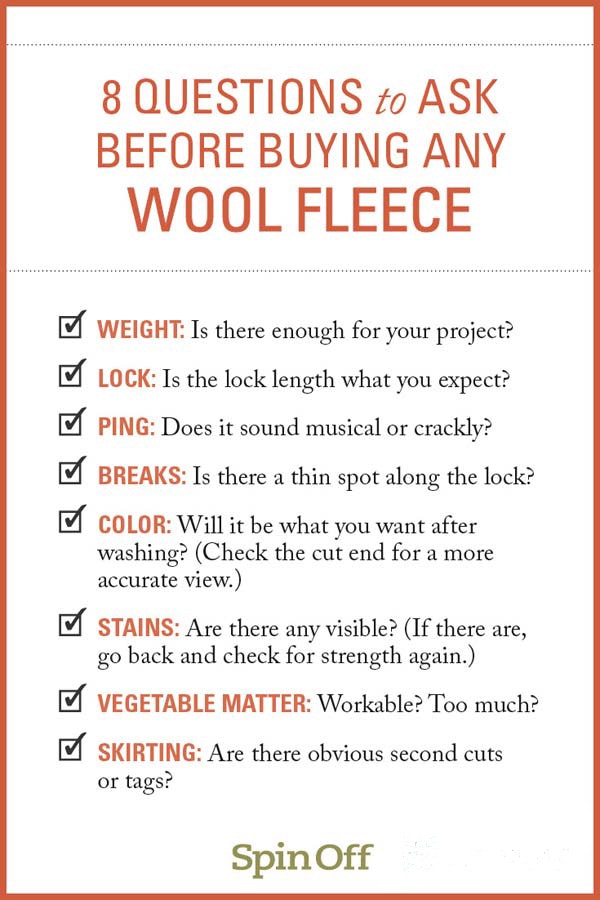

Fleece Checklist

Start Local

Your local shepherds need you. Start there. Every state has sheep farmers, and you can find them if you just do a little bit of searching. If there is a certain breed you want, then begin to search farther away. As you search for the fleece that you want, make sure to ask good questions, and be prepared for a fleece that is surprising in a good or bad way. If it’s not what you expected, just move on, chalk it up to learning, and know that the sheep are growing more wool as we speak.

Beth Smith is a passionate aficionado of wool, a frequent contributor to Spin Off, and the author of The Spinner’s Book of Fleece. Her videos Spin Thin and Spinning to Get Even are available from Long Thread Media. She lives with her family in Michigan.

Originally published May 7, 2020; updated July 22, 2022.