Spinning is a combination of art and science, philosophy and physics, intuition and logic. We’re taught to draft and join and spin, but only skill and experience can tell us how much twist is enough for a particular fiber. We learn the attributes of two-ply, three-ply, and cabled yarns but choose to do one or the other “because it feels right.” Perhaps this is why spinning is so satisfying: both halves of our brains—the intuitive, emotional side and the calculating, rational side—get a chance to shine.

There’s no better example of this than the pursuit of a balanced yarn. What is a balanced yarn? Aside from being the Holy Grail of spinners, it’s a yarn in which the twist of the individual plies is exactly balanced by the opposite twist of the plying. This is useful because it means the yarn is essentially at rest, with no tendency to kink or bias when you knit it up. “Spin a balanced yarn!” is a common injunction, but how do you get one? Well, there’s some logic and science involved—but only if you want them to be.

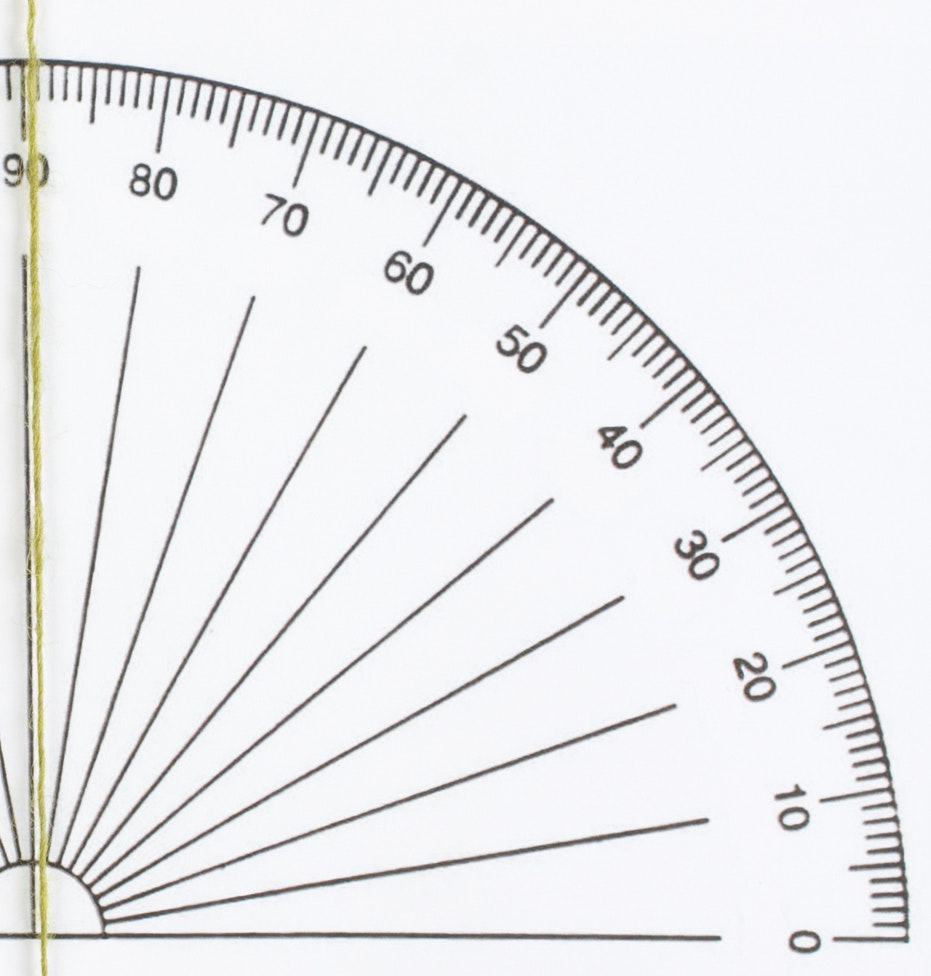

Singles spun Z-twist. The angle here is 68 degrees (90 minus 2), indicating that this yarn is slightly underplied.

Testing for Balance

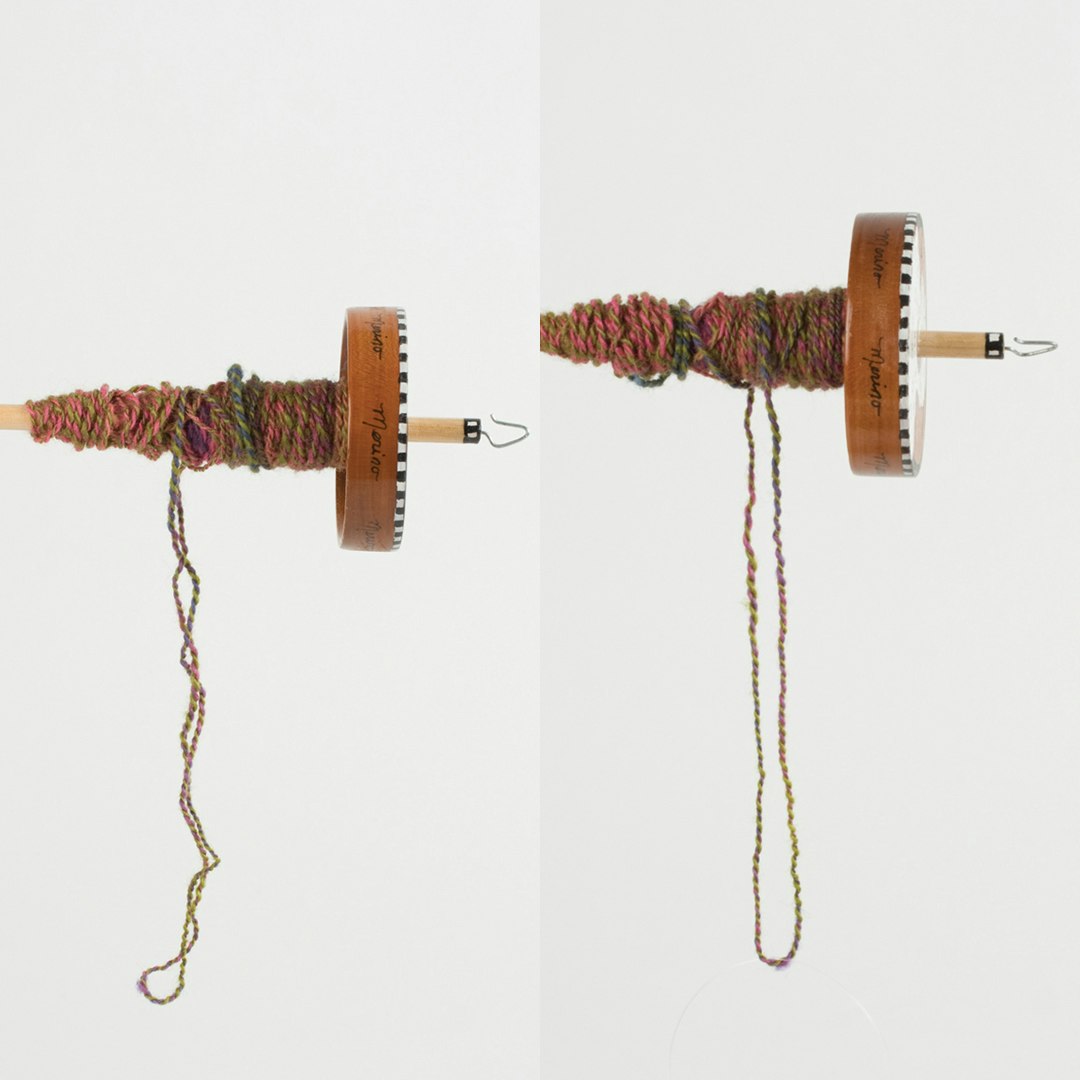

Here’s a simple way to get you close to that coveted balance point. Let’s assume you’re aiming for a twoply yarn, though you can look at three- or four-ply yarns using this method, too. Attach a spindle, or any other convenient weight (for example, an orifice hook), to the middle of a length of your finished singles. Pinch the doubled singles together a few feet above the weight and let the yarn dangle from your hand. The weight will start to turn in the plying direction, the opposite way from which your singles were spun (Z-twist if you spun S-twist, S-twist if you spun Z-twist). Why? Because the twist you put into your singles has been stored like the energy in a spring, and now you’re letting it uncoil. When the spinning stops, grab the weight. Test your yarn’s balance by doubling the now-plied yarn on itself and seeing whether it coils together (it shouldn’t coil if the yarn is balanced). You may not be exactly at your balance point because of the weight of the spindle or the moment of inertia (more on that on page 37), but you will be very close. This is what your balanced yarn should look like.

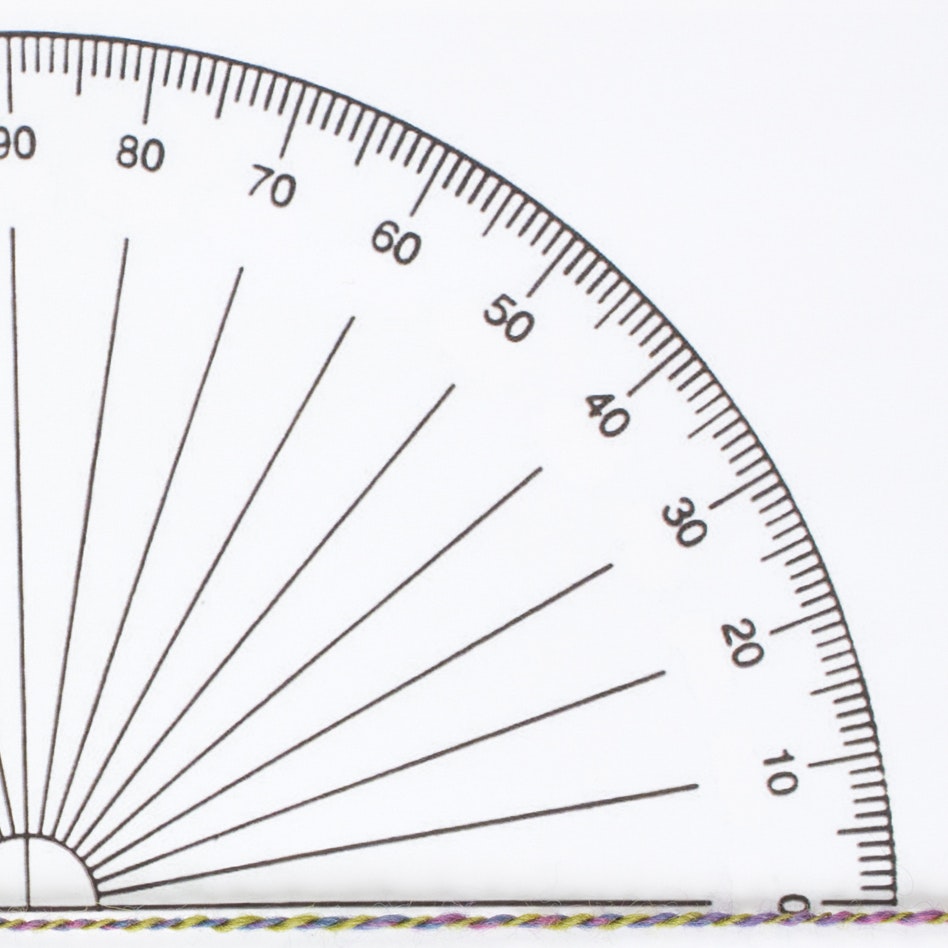

The 2-ply yarn has a 28° angle of twist.

Meeting Force with Force

So why does this work? Because balance is all about canceling the energy of the singles with the energy of the plying. Newton’s Second Law says force = mass × acceleration. Force is a vector, which means it has a direction, not just an amount. In the case of spinning, the force is called torque, the force around an axis—clockwise or counterclockwise. When you’re looking at a spindle or a column of fiber spinning itself into yarn, torque = radius × force. Again, torque is a vector; and if you add together two vectors going in exactly opposite directions, you get zero—which is where a balanced yarn sits.

Torque

This equation also means that all other things being equal, you get more torque if your spindle is bigger. You probably already knew this. You probably also knew that rim-weighted spindles spin longer. Why? Because of the moment of inertia, which is related to how far the mass is from the center of an object. A spindle that has most of its mass away from the center will have more inertia than a spindle that weighs the same but carries its mass close to the center. This means it takes more effort to get it going—but once it’s moving, it takes more effort (or friction and time) to stop it.

Theoretically, you could calculate the torque in each singles and figure out how much torque you need in the plied yarn. Thankfully, that’s not necessary. If no coiling occurs with the coil test already described, you’ll be pretty close to balance. If you’re satisfied with the yarn as it is, don’t bother reading further—keep your sample as a reference and ply the rest of your yarn. But if the balance isn’t quite there, there are easier ways to find it than digging out your old physics book.

First, you can try plying or unplying your yarn slightly. Yarn coils because it has an energy imbalance, and it relieves that imbalance by twisting in the opposite direction of the energy excess. Thus, if your yarn is overspun (too much plying energy), it will coil together in the direction of your singles, and if it’s underspun, it will coil in the direction of the plying. Add or subtract twist by turning in the same direction as the coil (Z if the coil is Z-twist, S if it’s S-twist), and you’ll get a balanced yarn.

(Left) The coil test also shows that the yarn is underplied. The coil is twisted in the S direction, which means there is too much singles (Z) spin and not enough plying spin. The small number of twists in the coil means it’s not underplied by very much. (Right) The yarn gets a few S-twist turns and becomes balanced.

Looking From a Different Angle

If you want to be more geometrical about it, take a look at the individual fibers in your yarn. When you spun your singles, they angled. When they are properly balanced in a plied yarn, those fibers will be vertical—that is, parallel to the yarn itself. But if you’re, say, 10 degrees off, how can you tell whether you’re 10 degrees underplied or 10 degrees overplied?

Take an angle that you’ve spun your singles to—let’s say 50 degrees from the horizontal. (Of course, not all of it will be 50 degrees, but this works out if you deal with averages.) If you’ve spun clockwise (Z-twist) the way most spinners do, this angle will be to the right—that is, if up is north, from southwest to northeast, like the cross-stroke in a Z. When you ply your balanced yarn, the angle of the singles winding around each other starts at 90 degrees (straight up and down) and becomes 50 degrees as well, but in the opposite direction—in this example, from southeast to northwest. (See http://www.knitting-and.com/ spinning/plied-yarn.html for an illustration of this.)

So what do you do? You ply, and you measure the angle created by the plies or compare it to your singles. If it’s smaller (again, with respect to the horizontal) than the original singles ply, you’ve overplied. If it’s bigger, you’ve underplied. Since you know the angle you’re aiming for, you can spin to that angle fairly easily by keeping your protractor handy or, eventually, by eyeballing it.

Despite all this, remember that a perfectly balanced yarn isn’t always necessary. Maybe your yarn is unbalanced, but it’s pretty and soft and strong, and making it balanced will destroy one of those qualities. If that’s the case, go with what will make the yarn more to your liking. In the end, creating a balanced yarn—or not—is about combining the physical realities of the fiber and the world with your intuition and your instincts about what feels right, which, really, is what finding balance should be about.

Jennifer Shafer of Toledo, Ohio, spins, knits, quilts, gardens, and writes. She learned to spin from a spindle kit purchased on eBay. She’s since graduated to a single-treadle Lendrum that she plans to keep with her ‘til death do they part.

This article was published in the Spring 2009 issue of Spin Off.