Subscriber Exclusive

Willowing Wool: Building Community by Sharing the Work

Riley Kleve discovered that an old way of fiber preparation can also build new friendships.

Riley Kleve discovered that an old way of fiber preparation can also build new friendships. <a href="https://spinoffmagazine.com/willowing-wool-building-community-by-sharing-the-work/">Continue reading.</a>

https://spinoffmagazine.com/cdn-cgi/image/format=auto/https://www.datocms-assets.com/75073/1736205858-graves-willowing-wool-2.jpg?auto=format&w=900

Like many handspinners, I frequently marvel at the fact that textile production was a facet of everyday life for most humans until the past couple of centuries. While I’m glad to live in our modern era—and in a city with a robust handspinning and weaving community—I can’t help but imagine past landscapes, living among neighbors who understand the process of turning raw fiber into functional cloth, sharing in the act of creation and maintenance of our work.

In my work as a teaching artist, I come across many people who want to create alongside others, both in classrooms and in more unstructured settings. I’m always looking for ways to connect people through textile work, particularly across generations and levels of expertise. After learning about wool waulking, a Scottish tradition for finishing woolen cloth revitalized by Marshfield School of Weaving founder Norman Kennedy, I began to imagine an analogue for handspinning. Waulking brings together a group to share the work of evenly fulling cloth through a kneading-like process, slowly at first and then faster and faster, calibrated to song. I wondered, is there a way to bring community into handspinning before waulking, before the yarn is even spun?

Willowing Border Leicester wool. Photo by Jesse Telephone

Willowing Border Leicester wool. Photo by Jesse Telephone

What is Willowing?

After some research, I found my answer in willowing, an antiquated fiber-prep technique used to open up locks and allow bits of vegetable matter, or VM, to fall out by hitting it with flexible willow branches. As is often the case with esoteric techniques, it’s difficult to track down much information about willowing. I first became acquainted with the concept while reading through The Alden Amos Big Book of Handspinning, with the following amusing description:

“Willowing is nothing more than spreading the picked, loose wool out on a coarse screen or lattice and flogging the hell out of it with a couple of smooth, limber sticks or switches. Hold one stick in each hand and whip away, right-left-right-left, and so on. You can work off petty frustrations while removing an amazing amount of junk from your fleece.”1

Amos recommends willowing a fleece before scouring, which opens up clumps of fiber so the scouring bath can fully permeate the fleece, then willowing again after it dries to help remove VM.

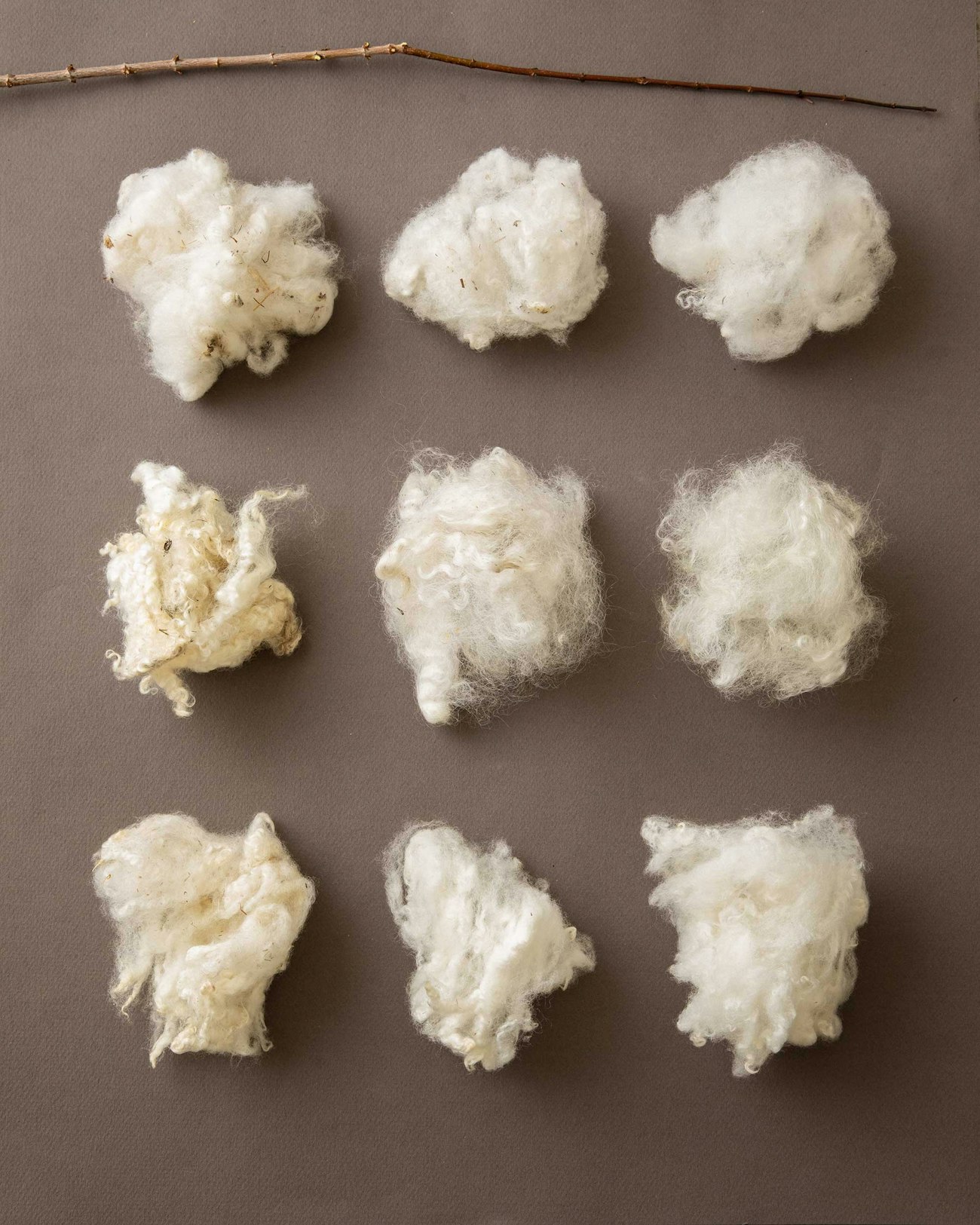

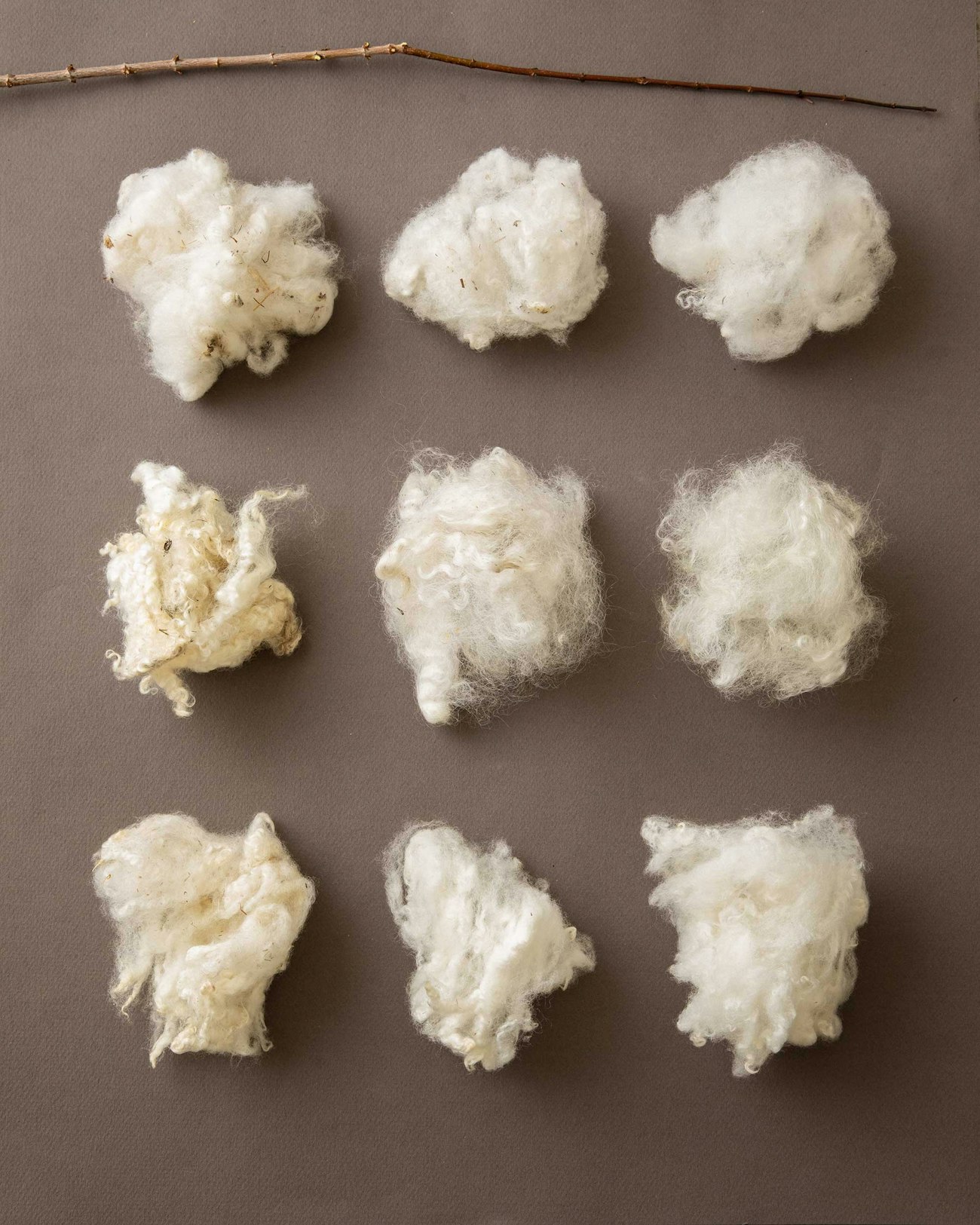

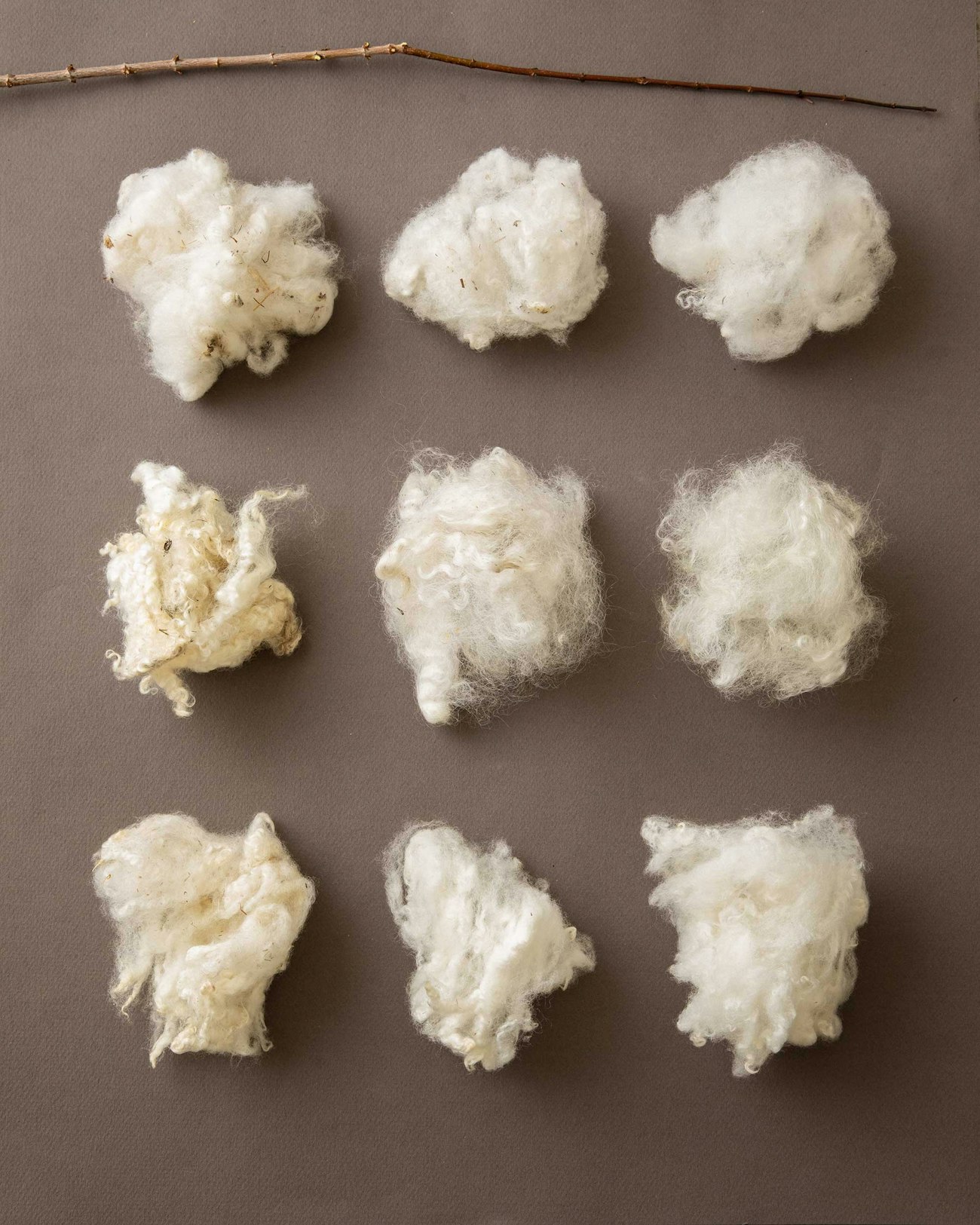

From left to right, each group of fibers has been scoured, then willowed once, then picked. From top to bottom: Polypay, Border Leicester, and Corriedale wool.

From left to right, each group of fibers has been scoured, then willowed once, then picked. From top to bottom: Polypay, Border Leicester, and Corriedale wool.

Willowing, Then and Now

During the Middle Ages, professionals as well as some lay people across Northern Europe would beat

SUBSCRIBER EXCLUSIVE

Like many handspinners, I frequently marvel at the fact that textile production was a facet of everyday life for most humans until the past couple of centuries. While I’m glad to live in our modern era—and in a city with a robust handspinning and weaving community—I can’t help but imagine past landscapes, living among neighbors who understand the process of turning raw fiber into functional cloth, sharing in the act of creation and maintenance of our work.

In my work as a teaching artist, I come across many people who want to create alongside others, both in classrooms and in more unstructured settings. I’m always looking for ways to connect people through textile work, particularly across generations and levels of expertise. After learning about wool waulking, a Scottish tradition for finishing woolen cloth revitalized by Marshfield School of Weaving founder Norman Kennedy, I began to imagine an analogue for handspinning. Waulking brings together a group to share the work of evenly fulling cloth through a kneading-like process, slowly at first and then faster and faster, calibrated to song. I wondered, is there a way to bring community into handspinning before waulking, before the yarn is even spun?

Willowing Border Leicester wool. Photo by Jesse Telephone

Willowing Border Leicester wool. Photo by Jesse Telephone

What is Willowing?

After some research, I found my answer in willowing, an antiquated fiber-prep technique used to open up locks and allow bits of vegetable matter, or VM, to fall out by hitting it with flexible willow branches. As is often the case with esoteric techniques, it’s difficult to track down much information about willowing. I first became acquainted with the concept while reading through The Alden Amos Big Book of Handspinning, with the following amusing description:

“Willowing is nothing more than spreading the picked, loose wool out on a coarse screen or lattice and flogging the hell out of it with a couple of smooth, limber sticks or switches. Hold one stick in each hand and whip away, right-left-right-left, and so on. You can work off petty frustrations while removing an amazing amount of junk from your fleece.”1

Amos recommends willowing a fleece before scouring, which opens up clumps of fiber so the scouring bath can fully permeate the fleece, then willowing again after it dries to help remove VM.

From left to right, each group of fibers has been scoured, then willowed once, then picked. From top to bottom: Polypay, Border Leicester, and Corriedale wool.

From left to right, each group of fibers has been scoured, then willowed once, then picked. From top to bottom: Polypay, Border Leicester, and Corriedale wool.

Willowing, Then and Now

During the Middle Ages, professionals as well as some lay people across Northern Europe would beat [PAYWALL] wool as part of the process of creating warm, woolen yarns free of VM. While it’s hard to say where exactly willowing was practiced, the term willowing’s analogues in French and Dutch (brisage de laines and wullebreken, respectively) give us some idea. In fact, commercial wool manufacturing has often utilized willowing machines to achieve the same ends on an industrial scale since at least 1890, documented in a trade manual that describes a large toothed drum that rotates along with three small rollers used to tease apart scoured wool and remove most VM.2

These days, willowing is no longer necessary for processing raw wool into a woolen yarn by hand. And yet, a few sentences in the Alden Amos book are enough to inspire a handful of intrepid spinners to try it. I imagine some Scottish people feeling similarly about carrying on with their waulking over the centuries; after all, water-powered fulling mills began to appear in Northern Europe in the 10th century and were quickly adopted nearly everywhere except for Scotland. Perhaps what kept their waulking alive was the community aspect, bringing people together through sharing work. If that is the case, I wondered if willowing could be used to similar ends, to gather as a community and share in the joy of creation. Eager to try it out, I set a date and time to hold a willowing workshop last June.

Willowing Corriedale wool. Photo by Jesse Telephone

Willowing Corriedale wool. Photo by Jesse Telephone

In an intro to Norman Kennedy’s From Wool To Waulking3 Anne Merrow writes that he gathered “a small group of handpicked friends who knew how a proper waulking was done.” Willowing, lacking waulking’s uninterrupted lineage of cultural practitioners, has no experts, so instead I turned to a variety of friends and colleagues as my new community of willowers.

Our numbers included handspinners, weavers, and dyers with interests spanning gothic linen tank tops, naturally dyed batts carded from local wools, crochet balaclavas in psychedelic hues, impeccable handwoven wedding wear, and theme-and-variation projects on a long warp. A craft historian, improvisational dancer, DIY punk photographer, craft dabbler, and a spouse rounded out our numbers. Fittingly, we met in a community garden that has hosted chess clubs, harvest festivals, and plenty of bonfires in the past. I sourced willow branches that had fallen from weeping willows in a park nearby, prioritizing branches that were more-or-less straight with a sturdy base and flexible end.

The group willowing Border Leicester wool. Photo by Jesse Telephone

The group willowing Border Leicester wool. Photo by Jesse Telephone

How Effective is Willowing?

I brought well-scoured fleeces from a few different breeds to willow, about two ounces of each. We started out with Polypay with slightly dirty tips and plenty of tiny VM scrambled throughout the locks. While willowing, the locks opened up nicely and easily went airborne along with our willow branches. A decent amount of the VM fell out of the fleece, with the exception of the clumpy tips. I’d imagine a flick carder would finish the job nicely.

We moved on to some Border Leicester, which had a lot of large pieces of hay and grass scattered along the long, curly locks, as well as tiny (infuriating) bits of unidentifiable VM. This fleece did not seem to willow very well—the locks retained their shape rather than fluffing up and separating into cloud. While none of the large pieces of VM were knocked loose (as expected), there are noticeably fewer pieces of smaller VM. After picking out the large bits by hand, the resulting wool is in decent shape.

Our biggest success was with a mystery wool from my stash, probably Corriedale (4" staple, good crimp pattern, relatively fine wool, and frankly more likely to wind up in an unlabeled bag in my stash than a more uncommon breed). There was a variety of VM present throughout the fleece. Most of it was small but not tiny, with an assortment of straw and grass for good measure. The locks opened up beautifully and stayed airborne nicely, emerging lofty and free from most VM.

Our willowing gathering was informal, with participants coming and going throughout the process. Frequently, the latest newcomer would ask what I planned to use the wool for. “I’m not sure yet,” I’d reply, “But I’ll invite you when it’s time to waulk whatever it becomes!”

The author inspecting Corriedale wool after willowing. Photo by Jesse Telephone

The author inspecting Corriedale wool after willowing. Photo by Jesse Telephone

Notes

1. Amos, Alden. The Alden Amos Big Book of Handspinning. Interweave, 2001.

2. Beaumont, Roberts. Woollen and Worsted Cloth Manufacture: Being a Practical Treatise for the Use of All Persons Employed in the Manipulation of Textile Fabrics. Accessed via Internet Archive.

3. Merrow, Anne. "Weaving and Waulking with Norman Kennedy,” HandwovenMagazine.com.

Special thanks to Barb, Jasmyn, Nina, Olivia, Reed, Snem, Trinity, and Tijqua.

Riley Kleve is a nonbinary artist and educator in Minneapolis. Their handspun and woven work mines archives to create a queerer future for textiles. Riley is currently in residency at North House Folk School and teaches handspinning and other textile classes regionally. They can be found online at @betterdaysyarn or Betterdaysyarn.co.

Willowing Border Leicester wool. Photo by Jesse Telephone

Willowing Border Leicester wool. Photo by Jesse Telephone From left to right, each group of fibers has been scoured, then willowed once, then picked. From top to bottom: Polypay, Border Leicester, and Corriedale wool.

From left to right, each group of fibers has been scoured, then willowed once, then picked. From top to bottom: Polypay, Border Leicester, and Corriedale wool.

Willowing Corriedale wool. Photo by Jesse Telephone

Willowing Corriedale wool. Photo by Jesse Telephone The group willowing Border Leicester wool. Photo by Jesse Telephone

The group willowing Border Leicester wool. Photo by Jesse Telephone The author inspecting Corriedale wool after willowing. Photo by Jesse Telephone

The author inspecting Corriedale wool after willowing. Photo by Jesse Telephone