So many of us choose the project after the yarn is spun, especially when we’re working with just 4 ounces of fiber. But what if you want to make a sweater or another large project? What wool do you choose? If you know more about the fiber, you can plan the project and not let the project plan you.

Some questions to ask

If you’re just starting out and don’t even know where to begin, here are some questions to ask.

- What type of garment are you making?

- Will it get a lot of wear and tear? Will it be subject to a lot of abrasion, such as the heels on socks?

- Will it be used occasionally? Perhaps it will be more decorative than serviceable?

- Is this item intended to provide warmth?

- Will the wool you are using give you the right amount of drape? Or will it have too much drape to retain its shape?

- Does your pattern have intricate stitch patterns such as cables? Will the halo of a particular yarn hide the stitch detail in your project, and is that okay?

Sheep wool

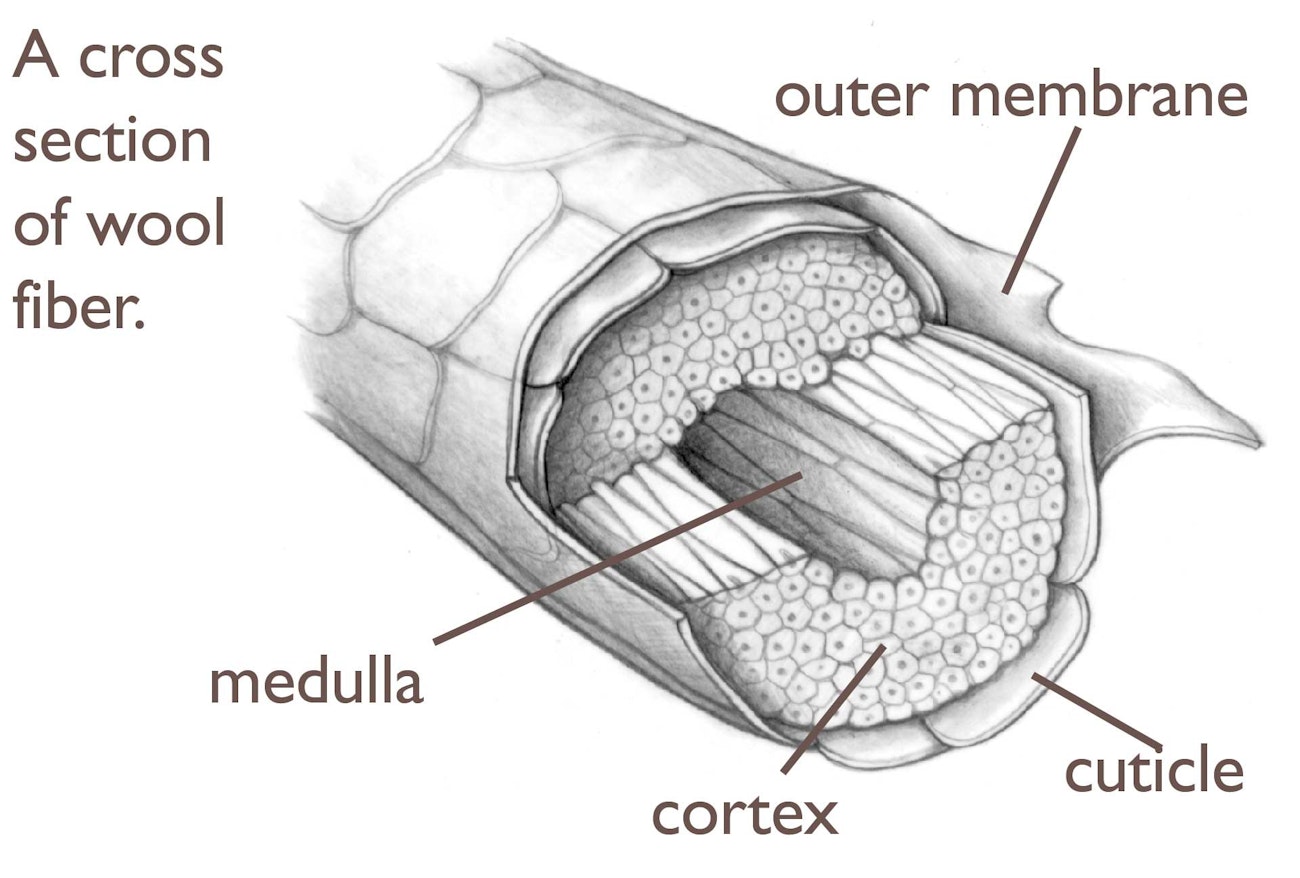

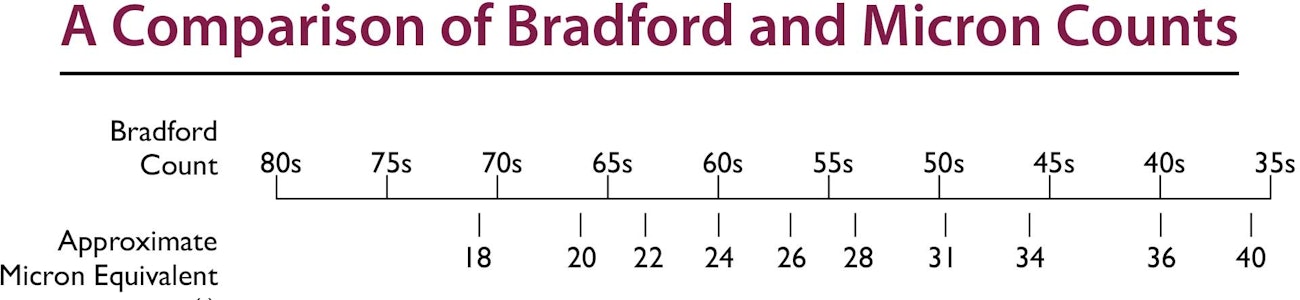

Wools are designated as fine, medium, or coarse as determined by the Bradford count system or by micron count. These terms refer to the diameter or thickness of the wool fibers. Other characteristics such as crimp, staple, and luster should also be considered when selecting fiber for a project. Generally, use fine wool for softness, longwools for luster and strength, and the down-type wools for their elasticity and resilience.

Fine wools

Fine wools feel softer than medium or coarse wools. However, fine wool fabrics don’t wear as well and are less durable compared to medium or coarser wool. Fine wool has an average fiber diameter of 90s to 60s on the Bradford count system, or 25 to 17 microns. It is excellent for fine, delicate, soft garments where the feel of the garment is important, such as baby wear or next-to-the-skin wear, especially around the neck. Fine wool produces a woven fabric that has excellent drape. Some of the breeds classified as fine wools include Merino, Rambouillet, Bond, California Variegated Mutant (CVM), Columbia, Comeback, Cormo, Corriedale, Debouillet, Dormer, New Zealand Halfbred, Panama, Polwarth, Polypay, Romeldale, Targhee, and Zenith. The finer wools have a heavy concentration of lanolin; therefore, the yield of clean fleece to raw fleece is only about 50 percent. If you are purchasing a raw fleece to spin, buy twice as many pounds of raw wool as you will need in a clean preparation, ready to spin. The average raw fleece for fine wool weighs 9.5 to 13 pounds, and the average staple is 3.5 to 5 inches.

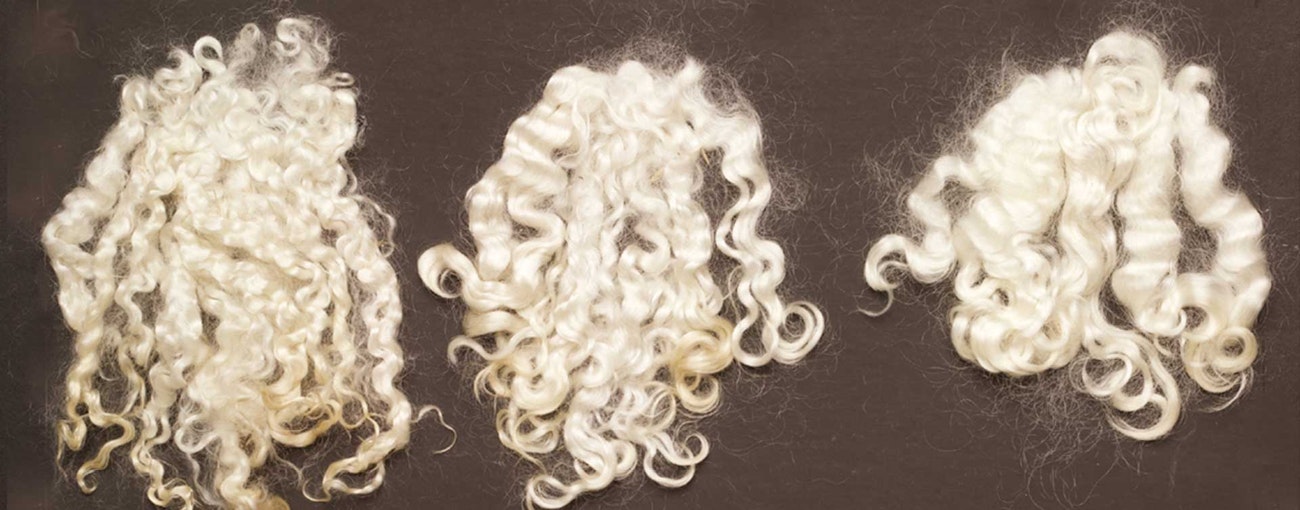

Longwool: Coopworth. (from left): Brown unwashed Coopworth lamb’s fleece; White washed; Unwashed Coopworth adult fleeces.

Longwools

Longwools have a larger fiber diameter than fine wools. They are hard wearing and are used to produce heavy knitwear and outerwear, and some are used for carpets. Longwools are considered lustrous and some have a silky handle. They can be spun worsted, and a longwool is ideal for spinning semiworsted, a technique that requires a long and sound fiber. Examples of longwool breeds include but are not limited to Bluefaced Leicester, Border Leicester, Coopworth, English Leicester, Finnish Landrace, Gotland, Lincoln, Masham, Perendale, Romney, Teeswater, Texel, and Wensleydale.

Down-type: Clun Forest. (from top) Scoured; Adult ewe Clun Forest wool in the grease.

Down-type wools

Down wools have a spiral crimp and exceptional elasticity and produce medium- to lightweight yarns that are great for knitwear yarns, socks, blankets, and tweeds. The spiraling form of the fiber tends to be crush resistant in woven fabric. Down-type wools are crisp with a spongy handle. The fiber diameter is fine to medium and the staple is 2 to 3.5 inches. The fiber is actually longer than the staple (which is measured without stretching the fibers) due to the spiral crimp of the fiber. Down wools have short staples and should be spun with considerable twist to hold the fibers in place. They are best spun woolen instead of worsted because the springy nature of the fiber creates a full, round yarn that is lusterless, with a chalky appearance. True down breeds originated in southeastern England, and some of the original down breeds include Southdown, Suffolk Down, Hampshire Down, Dorset Down, Oxford Down, and Shropshire Down. Cheviot, Clun Forest, Shetland, Suffolk, Tunis, and Welsh Mountain are just a few of the other down-type breeds that exist today.

Double coated: Scottish Blackface. (from left) Washed Scottish Blackface wool; Unwashed.

Double-coated fleeces

Sheep with double-coated fleeces have a long, hairy outercoat that protects the animal from the elements and a short, fine undercoat that provides insulation. The fleece is fairly open and airy. The outercoat has a slight wave or no crimp, while the undercoat has a crimp proportional to the fineness of the fiber. Both coats can be processed together (providing a fiber with coarse grade for outerwear) or dehaired (the two coats are separated). The undercoat by itself is considered a fine fiber and is often suitable for next-to-the-skin garments. The diameter of the outercoat limits the use of the wool when the two coats are used together. These dual- or double-coated breeds have little grease or lanolin, and therefore produce a high yield of clean to raw fleece. Care must be taken when handling the dual coats to avoid separating them while preparing the fiber for spinning. The undercoat will tend to felt easily, but the outercoat will felt little, if at all. Some double-coated breeds are Icelandic, Karakul, Navajo Churro, Romanov, Rough Fell, Scottish Blackface, Spelsau, and Swaledale.

Mohair. (from left) Fall kid, first clip, 23–30 microns; Spring kid, second clip, 23–30 microns; Yearling, third clip, 31–35 microns.

Goat fiber

Mohair

Fiber produced by the Angora goat is not called angora, but rather mohair. Mohair can vary from 14 to 90 microns; the finest mohair is referred to as kid mohair. Typically, kid mohair comes from a younger goat, but an older, well-bred goat may have less than 1 percent of medullated fibers (medullated, or kemp, fibers have a hollow core—see page 56), and its fiber can still be classified as kid. The epidermal scales in mohair are faintly visible, scarcely overlap, and lie close to the stem with a very smooth appearance. These properties allow the smooth surface to reflect light, giving it a beautiful luster, and mohair has much less tendency to felt than wool. Kid mohair blended with fine wool will produce a strong fiber that drapes and dyes beautifully.

Cashmere. Australian raw cashmere in a variety of hues.

Cashmere

Cashmere, a luxury fiber that has warmth without weight, outstanding drape, and incredible hand, comes from goats that produce a very fine undercoat or down. Cashmere is a type of fiber and does not come from a specific breed of goat. The down is soft and wavy with silklike fibers, whereas the outercoat (called beard hair) is harsh. Medullated fibers are absent in the undercoat but very pronounced in the outercoat. The greater the difference between the diameters of the two coats, the easier it is to dehair cashmere. Cashmere fiber is composed of scales projecting slightly beyond the cortical (outer) layer that are elongated, very smooth, and almost undetectable, giving cashmere a wonderfully soft hand. To be labeled cashmere in the United States, the fibers must have a micron count of 19 or finer, with less than 3 percent by weight of fibers exceeding 30 microns. To be classed as cashmere, the fiber must have a distinct crimp that changes directions at random intervals along the length of each individual fiber. This crimp structure allows the fiber to hold lots of air, making cashmere an incredibly warm but lightweight fiber that retains its shape incredibly well. If the fiber lacks this character, it would be classified as cashgora (a less valuable fiber).

Pygora. (lower left) Washed type A pygora fiber. (upper right) Raw type A pygora lock.

Pygora

Pygora goats have fiber that is classified into three types: A, B, or C. Type A describes a fine, silky, mohair-type coat that doesn’t coarsen with age. Type C, a true cashmere coat, and Type B, a combination of Types A and C, exhibit staples of 3 to 6 inches with a wavy crimp. Pygora fiber contains guard hairs that need to be separated from the softer undercoat.

Camelids

The camelid family includes camels, llamas, alpacas, vicuñas, and guanacos. Camelid fleeces require dehairing to separate the harsh outercoat from the finer undercoat, with the exception of fleece from alpacas, which have been bred to have a single coat that is fine and long.

Camel. Bactrian camel down in seven natural colors.

Camel

The camel has three distinct coats: a harsh outercoat that can be up to 15 inches long, a middle coat that is similar to fine sheep’s wool, and a soft inner coat that is similar to cashmere. The down or inner coat of the camel ranges from 9 to 40 microns, with the average staple at about 18 microns. The inner coat is usually spun woolen, and the incredibly soft fibers are primarily used for very fine cloth and lace. The middle coat is used to make artists’ paintbrushes, and the harsher outercoat makes good warp yarns for rugs and can be woven for tents.

Paco-vicuña. Paco-vicuña is a cross between an alpaca and a vicuña—the result is a very fine fiber (14–23 microns).

Alpaca and Llama

Alpaca ranges from 10 to 60 microns, with an average of 26 to 28 microns. The alpaca’s fiber is a hair, rather than wool, with a medulla filled with lots of air sacs, making it great for heat retention, and giving alpaca fiber great insulating properties without adding weight. Alpaca does not contain lanolin and is a great alternative for someone sensitive to lanolin from sheep’s wool. Alpaca fiber is about three times stronger than wool and becomes even stronger when wet. Alpacas are of two distinct types: huacaya, with a fine, dense, and somewhat crimpy coat ranging from 18 to 27 microns, and suri, with fine, straight, almost silky fiber ranging from 10 to 15 microns.

Llamas are double coated; the outercoat protects the animal from the harsh elements and the softer inner coat is springy and made up of medullated fiber that lacks oil and wax and has little odor. Llama fleeces tend to be full of dust and dirt and need to be washed before prepping.

Vicuña and guanaco

Vicuña is considered the finest fiber in wool manufacturing and varies from golden chestnut to a deep, rich fawn color. Vicuñas, too, have dual coats, and the inner coat is a prized possession, not only for its incredible softness, but because of the limited supply—the coat is harvested every three to four years. Vicuña ranges from 6 to 25 microns with an average of 13 to 14 microns. Guanaco is another rare fiber that falls between alpaca and vicuña in fineness, with an average micron count of 18 to 24 microns.

Angora. The Satin angora breed was developed from crossing a French Angora with a short-haired rabbit for angora with an unusual luster and intensity of hue.

Angora rabbit

When you hear the term angora, it is in reference to the fiber, or actually fur, from an Angora rabbit. The Angora rabbit is actually a phenotype, not a specific breed or genotype. Three breeds of rabbit that produce angora are English, French, and German rabbits. Each breed varies slightly in the type of fiber it produces. English Angora rabbits have the softest coat with little guard hair, and the fiber is the most like cashmere. French rabbits have more guard hair and produce more fur-like fiber. German rabbits are the largest and, therefore, produce the most fiber. The German rabbit has a somewhat coarser fiber than either the English or French, but nonetheless it is an incredibly soft and shiny fiber. Angora fiber contains medullary cells, and the fur is arranged in a ladderlike fashion with discontinuous medullas arranged in single row cells that are round, disc-shaped, or pocket-shaped. Between the medullary cells are air spaces or vacuoles that give angora fiber its incredibly warm insulating properties. The scale structure is coronal, with one scale surrounding the fiber completely. The free scale ends are parallel to each other, running crosswise as in fine wool or in twist fashion from right to left (S-twist). The undercoat ranges from 8 to 30 microns and the guard hair from 30 to 150 microns.

Conclusion

Fine wools blend well with other fine fibers such as silk, angora, and kid mohair to create new and exciting possibilities for your yarn. Blending wool with cashmere or alpaca will add elasticity without sacrificing the softness. Adding angora will create a wonderful halo effect and a sensuous softness that is out of this world. Think of the limitless possibilities for combining fibers to create the perfect yarn for your project!

Diane Lalomia lives in northwest Michigan with her husband and son on their farm, Bella Vita Farm & Fiber, bellavitafarm.com, where they raise Finn sheep. She knits, crochets, spins, and recently learned to weave.

This article was published in the Spring 2010 issue of Spin Off.