Many of you may have heard of the Berta’s Flax project, started by Christiane Seufferlein in Austria. A neighbor gifted her a dowry chest filled with flax grown and prepared in the 1940s. Berta was the name of the woman who had once owned the chest. Christiane posted on social media, asking fellow spinners if they would like to have some of Berta’s flax. In early 2021, Christiane started shipping Berta’s flax stricks to spinners, and she was then contacted by other families who had flax dowries. A long line of Austrian women’s flax dowries have now been passed through Christiane to enthusiastic spinners around the world wanting to honor the memory of Berta and her flax-dowry sisters. I was one of those spinners.

In one of the numerous articles about the project, Christiane was pictured wearing a plant-fiber shawl that I later learned was knitted from Nepalese nettles. I admired the shawl and played with the idea of knitting a similar one for myself.

The sometimes century-old Austrian flax has an exquisite quality. All the steps from sowing and growing to retting and processing have been performed with remarkable skill and dedication. And why shouldn’t they have been?—this was vital life insurance for the women of the time. I spun my strick of Austrian flax with love and reverence in the shade on my balcony during a couple of summers.

Left: The author spins her Austrian flax on the flax wheel she named Henrietta after her great-grandmother. The blouse she is wearing used to belong to her great-grandmother. Photo by Josefin Waltin. Right: Josefin is shown wearing the Veela lace shawl. Photo by Dan Waltin

Left: The author spins her Austrian flax on the flax wheel she named Henrietta after her great-grandmother. The blouse she is wearing used to belong to her great-grandmother. Photo by Josefin Waltin. Right: Josefin is shown wearing the Veela lace shawl. Photo by Dan Waltin

I bought a flax wheel that I decided to call Henrietta, after one of my Austrian great-grandmothers. Her daughter, my grandmother Elly, came to Sweden from Vienna with the Red Cross buses after World War I at the age of 14. She quickly fell in love and stayed in Sweden, leaving her mother and her best friend behind. My great-grandmother took the train numerous times from Austria to Sweden to visit her daughter. Later, Elly took the train to Austria with her family to visit her childhood friend, who later became my other grandmother.

Flax to Linen

I hadn’t spun very much flax at the time; I didn’t think I was good enough to allow myself to handle the antique golden fibers that had been grown and prepared with such skill. But this was the time. I had grown my own flax for eight years, and I couldn’t hide behind my high standards anymore. I read a lot and came across literature that described how flax fibers naturally turn counterclockwise. For that reason, the recommendation was to follow the natural twist in the fibers and spin it in the same direction. And so I did. As I didn’t trust my flax-spinning skills enough to use the yarn as singles yet, I plied it clockwise.

My original plan for the yarn was to weave with it. However, the memory of Christiane’s nettle shawl poked me with a firm rhythm, and I decided to realize my plan to knit something similar. The linen yarn was the perfect candidate for the project. I found a pattern with a chevron lace center and a lace edge with columns of yarnovers that resemble knitted fringe.

Knitting on the train through Denmark. Photo by Josefin Waltin

Knitting on the train through Denmark. Photo by Josefin Waltin

I started to knit the lace edge on the train to Austria with my family later that summer. As the thread went through my quite exhilarated fingers, I thought about Henrietta and my grandmother and how they must have missed each other; about the two childhood friends, my grandmothers, who met in the Austrian lake district of Salzkammergut with their own families in the 1950s; and about my parents who, after having fallen in love, made the same train rides between Vienna and Stockholm to see each other in the early 1960s. My reflections on the moving train knitted themselves into the open lace through southern Sweden, across the flat landscapes of Denmark and Germany, and down to the beginning of the Alps in southern Bavaria, to arrive 24 hours later at our destination of Salzkammergut, not so far from the soil that once had nurtured the flax as well as my grandmothers and my father.

Knitting with linen yarn is quite different from knitting with wool. Linen yarn has no elasticity, no give. Fingers that are used to an accommodating wool yarn will be slightly offended by the brusque pull of its linen cousin. I realized that a shawl of the size I was knitting wouldn’t be finished in a heartbeat and that it would benefit from the company of a parallel project. After all, a treasure like this can’t afford to be left unfinished due to sore fingers.

The lack of elasticity of linen gives the fabric a drape that is unachievable with wool yarn. Compared to commercial linen yarn, the drape of handspun linen yarn will reveal itself as even more dramatic due to its weight. Throughout the summer, I have giggled underneath the impressive length of that lacy textile, feeling like a queen wrapped in a smooth and cooling magic mantle, from my knitting hands down to my toes.

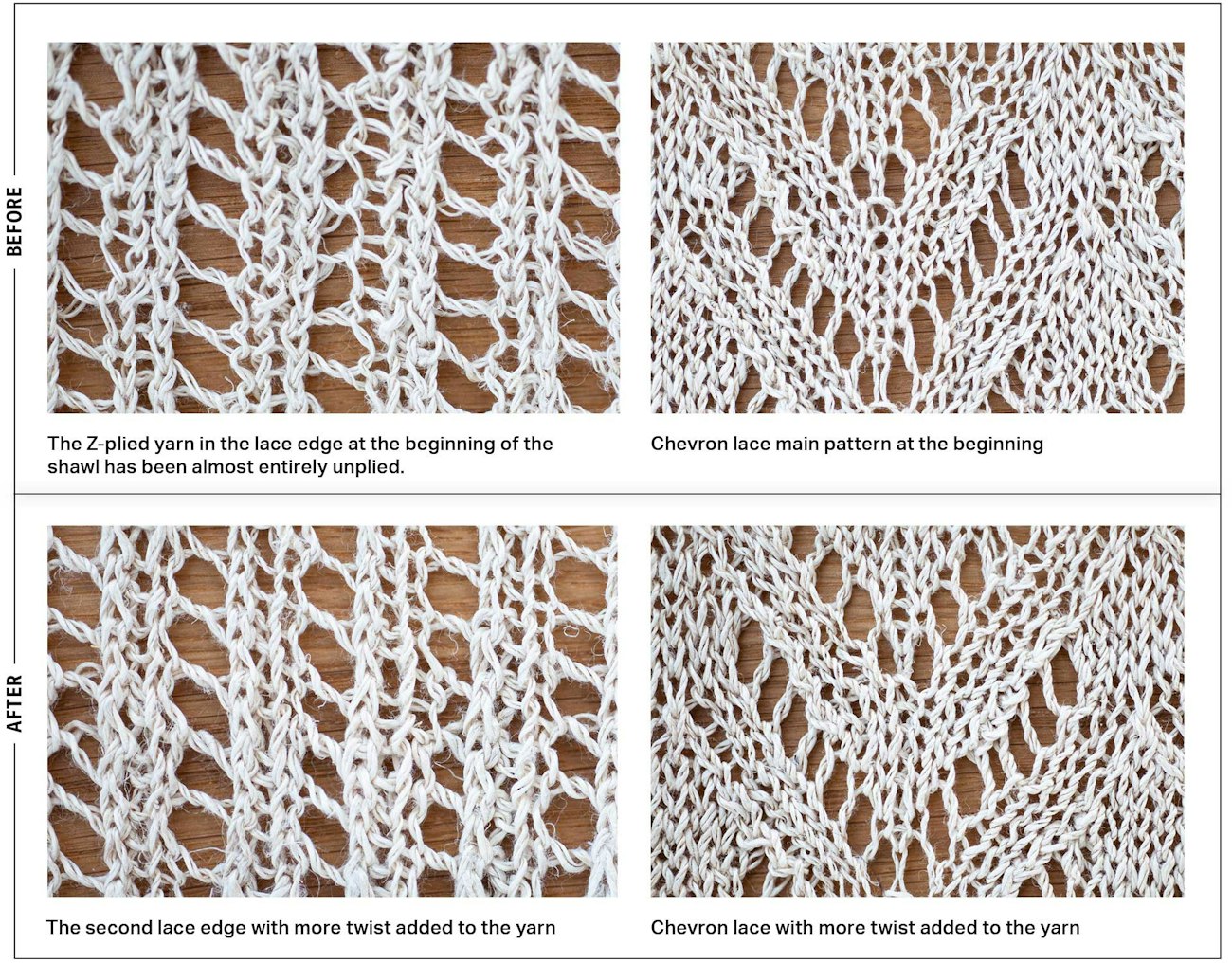

In the slow progress of working through the lace structure, I had time to observe the details. It dawned on me that the two plies of my yarn had settled next to each other in the fabric rather than twisting. My yarn was spun and plied in the opposite direction of a regular knitting yarn. As I was knitting, I therefore inevitably unplied my clockwise-plied linen yarn. What’s more, the knitted fabric objected and leaned the other way in protest, leaving a biased fabric. However, in my eagerness to see the fabric unfold between my hands, I had started knitting before I had enough yarn. After having discovered my somewhat embarrassing biasing mistake, I added extra plying twist to the rest of the skeins to save the remaining part of the shawl from the fate of an uncomfortable angle. The chevron lace stayed straight, while the end “fringe” was a little less biased than at the beginning. As I later blocked the finished shawl, the bias relaxed and doesn’t really show to the untrained eye.

Since early in my spinning life, I’ve known—the hard way—that my mistakes are a map of what I have learned. This is, of course, true for my linen shawl, too: every time I see those parallel singles in the ply, I am gently reminded that my knitting yarn shows its most flattering side when it is spun clockwise and plied counterclockwise. Also, I spun the yarn from skeins from different chests of the Austrian flax. At one end of the linen shawl, the color of the flax is slightly darker than the rest of the shawl. And that is how flax works. Depending on weather, location, retting, and climate, the color can differ between harvests. It is a sweet reminder that flax is a natural material and that nature is perfect in its imperfection.

Threads of Connection

I write this in midwinter. Sometimes I sneak into my wardrobe to cuddle with the linen shawl. Every time I stroke my hands across the lace, I am taken back to that rocking train, back to my roots and the train rides through generations, back to my family crossing borders to be together.

Left: Christiane Seufferlein and Josefin met in Stockholm on a summer day. Christiane is wearing another Nepalese nettle shawl and Josefin is wearing her finally finished linen shawl. Right: Josefin bought more Austrian flax from Christiane when they met in Austria. Photos by Josefin Waltin

Left: Christiane Seufferlein and Josefin met in Stockholm on a summer day. Christiane is wearing another Nepalese nettle shawl and Josefin is wearing her finally finished linen shawl. Right: Josefin bought more Austrian flax from Christiane when they met in Austria. Photos by Josefin Waltin

While in Austria that summer, I spent a day in Salzkammergut with Christiane. She wore the lace shawl I had admired so. I showed her my lace knitting and told her about the inspiration behind it. She instantly took off her shawl and gave it to me, and I treasure it. This year, Christiane came to Sweden, and we spent a day together, she in another Nepalese nettle shawl and me in my finally finished Austrian linen lace shawl.

Resources

- Berta’s Flax, facebook.com/groups/279258827044398.

- Bertas Flax: International Flax Guild, bertas-flachs.at.

This article was first published in Spin Off Summer 2024.

Also, remember that if you are an active subscriber to Spin Off magazine, you have unlimited access to previous issues, including Summer 2024. See our help center for the step-by-step process on how to access them.

Josefin Waltin started spinning in 2011. She is a spinning teacher, offering lectures and workshops both online and in person, mainly in spindle techniques and processing raw fleece into finished yarn. Josefin is a freelance writer, publishes instructional and documentary-style videos, and manages a spinning blog from her home in Sweden at waltin.se/josefinwaltinspinner.