The craft of spinning is laden with old wives’ tales. Its roots are in the earliest history of humankind, so we’ve had centuries to create an extensive mythology around our craft.

Here are just two of the old wives’ tales that have been making the rounds since I started spinning almost fifty years ago:

- Handspun yarn is not suitable for a warp—use it for weft only.

- If you do try to weave with a handspun warp, it must be plied.

It’s pretty easy to dismiss the first of these. Just go to any museum that has textiles predating the Industrial Revolution, and you’ll see that they’re all handspun, every last bit of them, warp and weft both. So why have so many of us modern weavers, with our wonderful wheels and looms, bought into the myth that we can’t use our handspun for warp? Probably for a couple of reasons.

First, our looms. Jack, or rising shed, looms, really are harder on warps than the more traditional counterbalance or countermarch ones. Every warp thread is required to stretch a considerable distance, over and over again, to create a workable shed. Rigid-heddle looms present even more of a challenge: the “hole” threads rise and sink again and again, while the ones in “slots” remain in a neutral position.

Second, the way we spin (or spun). When spinning was experiencing its umpteenth renaissance in the 1960s and 1970s, most spinners were working with wool, often uncarded or even unwashed, and they were producing soft, uneven yarns—yarns with slubs that could easily drift apart or become seriously abraded by heddles and beaters. It’s quite true that these yarns were not suitable for warps!

What about singles?

So let’s set aside the notion that we can’t spin our warps. Of course, we can. We simply need to spin yarns that have enough twist not to drift apart, enough stretch to make a good shed without self-destructing, and enough consistency not to get hung up in the loom apparatus. (Add to that enough smoothness not to get tangled with adjacent warp threads—but more about that later.)

But what about singles? Are they inherently too fragile to withstand the wear and tear? Well, it depends (like most things in our subtle craft). Look at old linen or silk damask fabrics from days of yore. More often than not, they are singles in both warp and weft whether they are really old (woven on handlooms) or newer (woven on industrial looms, which are not exactly gentle on the warp threads). Of course, both flax and reeled silk have very long fibers. If they have been spun with sufficient twist, and perhaps have appropriate sizing (more about that later), they are pretty indestructible.

Linda's fuzzy plaid fabric for a jacket.

Linda's fuzzy plaid fabric for a jacket.

A singles wool warp presents more challenges. A longwool, spun worsted with a fair bit of twist, should present no problems. What about a shorter fiber, softly spun—is it possible? It is. Look at the fuzzy plaid fabric above. When I spun the jacket fabric from space-dyed top, I was aiming to keep the colors distinct. Plying would have muddied them unless I had Navajo-plied, which my hands don’t do so well. I also wanted a fuzzy, slightly fulled fabric, so I split the top into thirds and spun it in a sort of hybrid woolen-worsted method that resulted in a soft yarn without a lot of twist—about 8 twists per inch on average. As you can see, it made cloth, and warp breakage was almost nonexistent.

But that was top. What about picked wool? Many years ago, my then-young son raised some Corriedale sheep, and we had a little family project of turning one of his fleeces into a blanket. We had the fiber commercially washed and picked (not carded). I spun the yarn from the resulting mass of fuzz, and he (age eleven) wove it. Both warp and weft were singles. More than twenty years later, the blanket abides (see photo at top). The keys to success were warp sizing (see recipe at bottom), choice of weave structure (broken twill), and a wide reed. These latter choices meant minimal abrasion of the warp threads against their neighbors.

Left: Linda’s scarf is made with handspun cotton blended with silk. Right: Linda found this old cotton pillowcase at a junk shop years ago—it inspired her to weave with singles warp and weft.

Left: Linda’s scarf is made with handspun cotton blended with silk. Right: Linda found this old cotton pillowcase at a junk shop years ago—it inspired her to weave with singles warp and weft.

Cotton? Are you kidding?

It would never have occurred to me that you could make a decent cotton singles warp until I started to closely examine the old pillowcase above. I picked this up in a junk shop years ago. Here’s what’s embroidered on it: 1820/spun by Mrs. J. Albertson in 1865/1905. I don’t know quite what all those dates mean, except that it is handspun, and it is old. Most amazingly, it appears to be cotton, and both warp and weft are singles. The fibers are short and very fine. I imagine a great wheel.

The little scarf, on the other hand, is spun from a blend of cotton and very short tussah silk. There’s a lot of twist in the yarn, and the tussah, short though the fibers are, tends to “grab” the cotton, making for a very sturdy little singles that posed no problems in the warp.

Left: Rigid-heddle looms put stress on every other warp because the warp threaded through the hole rises and sinks, while the warp threaded through the slot remains in a neutral position. Right: Rising shed looms are harder on warps than counterbalance looms because they stretch the warps a considerable distance to create a shed. Illustrations by Ann S. Swanson

Left: Rigid-heddle looms put stress on every other warp because the warp threaded through the hole rises and sinks, while the warp threaded through the slot remains in a neutral position. Right: Rising shed looms are harder on warps than counterbalance looms because they stretch the warps a considerable distance to create a shed. Illustrations by Ann S. Swanson

Why use a singles warp? And what are the tricks?

According to Judith MacKenzie, you should have a very good reason for using a singles warp, saving time not being one of them. For my projects, I liked the way an all-singles wool fabric fulled, though I confess I didn’t sample with a plied warp. I liked the way the cotton/silk, highly twisted, resulted in a crepey fabric. The old pillowcase? Who knows? Maybe Mrs. Albertson couldn’t spin a thin enough yarn to ply it and still have a fairly fine, supple fabric. (Or maybe she was in a hurry.)

As for making it work, here’s what I’ve learned from my limited experience:

- Put enough twist in your fiber and try to spin a fairly consistent yarn. You don’t need to overdo this, but just be sure you don’t have soft spots that will drift apart.

- Test the strength of your warp. Don’t judge your yarn by tugging on a single thread—tug on a whole bundle, maybe a dozen or twenty threads. A whole warp is stronger than any single element.

- If you’re weaving with wool and you want your fabric to full nicely, don’t wash or block your warp before weaving it.

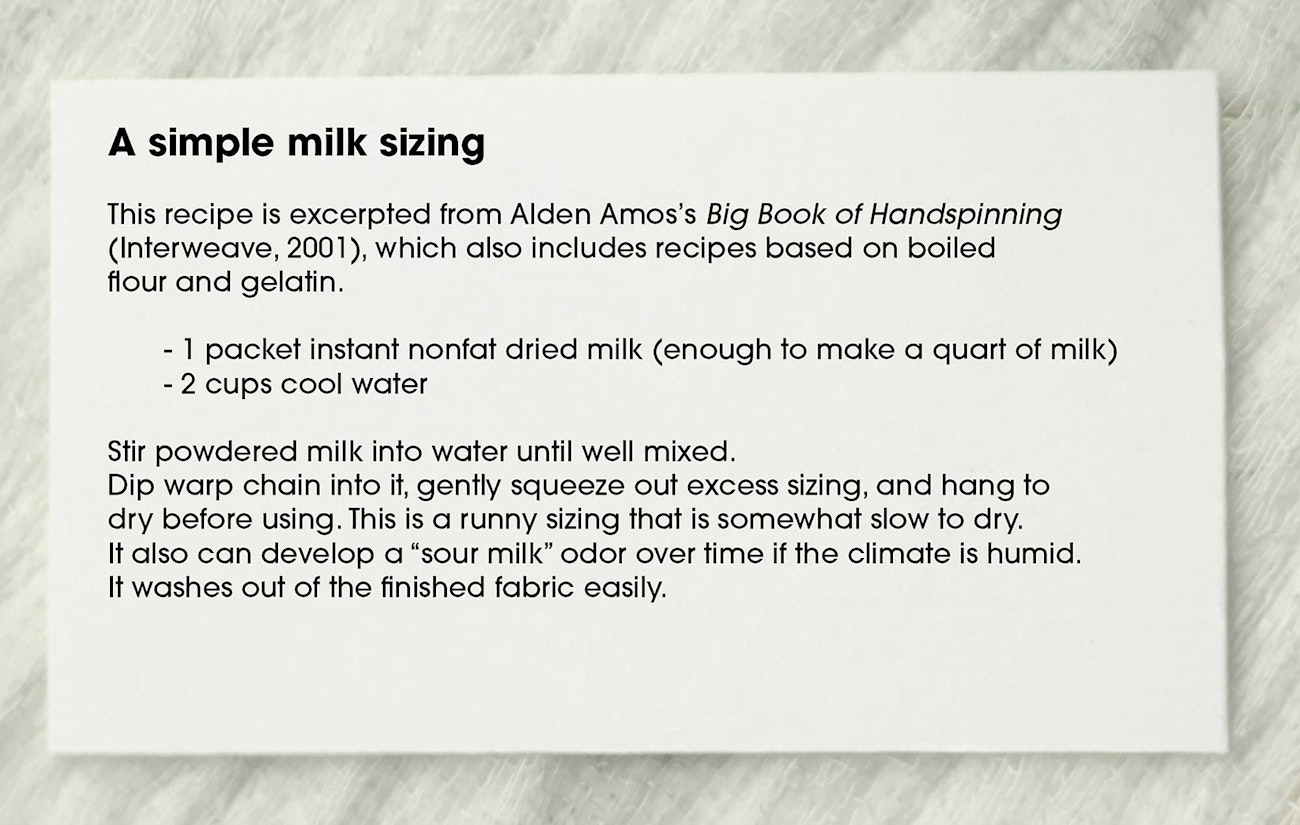

- If your warp is at all fuzzy, put a warp sizing on it so the threads won’t tangle with their neighbors. There are a number of glue-based products on the market for this purpose, but the milk sizing recipe at left has been perfectly adequate for my needs, and it’s always right there in my pantry.

- Dress your loom gently. I like to warp from back to front so the warp threads don’t have to go through the reed and heddles but once. I use a raddle, but once I’ve tied onto the back beam, I remove the back lease sticks to eliminate drag. I also keep my warps fairly short—no more than 6 or 8 yards at most.

- Take it easy. Be sure your shed is clear before throwing the shuttle; don’t let your selvedges draw in too much. Have enough extra warp thread to make repairs if you need to. That’s it.

Linda Ligon is one a co-founder of Long Thread Media.

This article was first published in Spin Off Summer 2010. Published to web December 9, 2020; updated May 5, 2025.